Some of the copper cremains containers still have their original labels at the Oregon State Hospital Memorial on Wednesday.

In 2004 a group consisting of a legislator and a team of journalists stumbled upon a ghastly sight while touring the Oregon State Hospital. They discovered a dusty forgotten shed-like structure with over 3,500 copper tins with unclaimed human cremains inside. It was referred to as the “room of forgotten souls.”

There is now a memorial, which is a recreation using the original copper canisters as they were found in 2004.

The remains were removed from the cans and placed in ceramic urns which are now inside the concrete walls of the memorial. Each has the name, birth, and death of each person’s remains. The memorial is meant to honor the people and store their cremains.

Phyllis Zegers, a Roseburg genealogist, aims to reunite the cremains of the forgotten souls with their living family members.

“OSH returns ashes to families once a year, typically in September,” Zegers said. “This September 127 were returned. Overall about 650 families have received ashes that I have informed them about. In total OSH has returned 695 urns to families.”

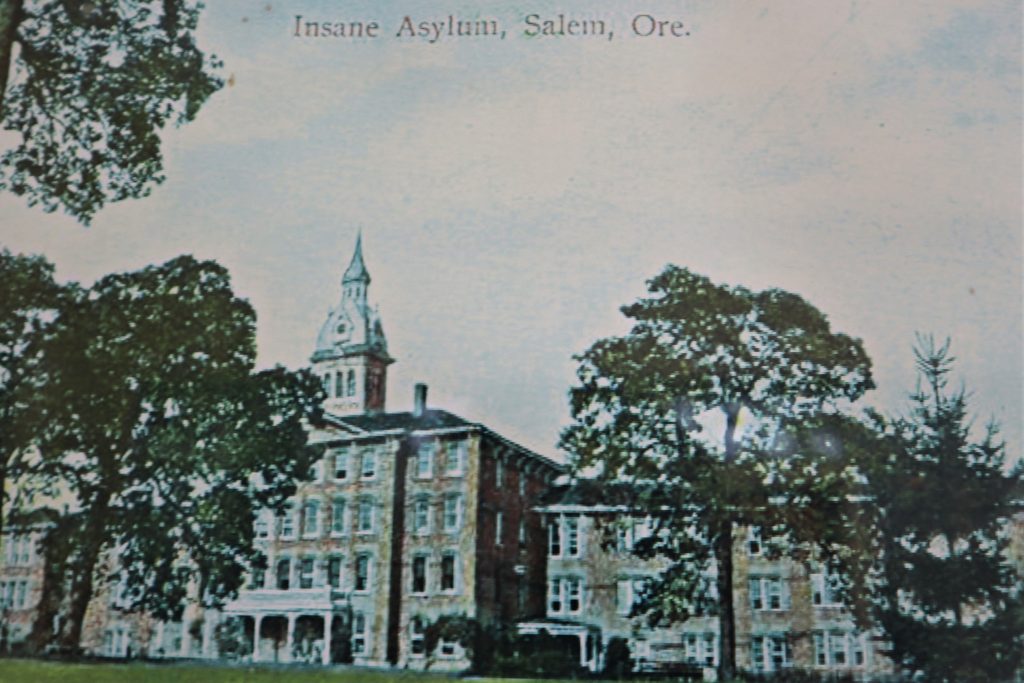

Oregon State Hospital which opened in 1883 as Oregon State Insane Asylum, changed its name in 1913, and was active in electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomies, eugenics, and hydrotherapy. In the early 2000s, the hospital received disapproval for its run-down facilities, treatment of patients, and the hospital’s management of over 3,500 canisters of unclaimed human cremains.

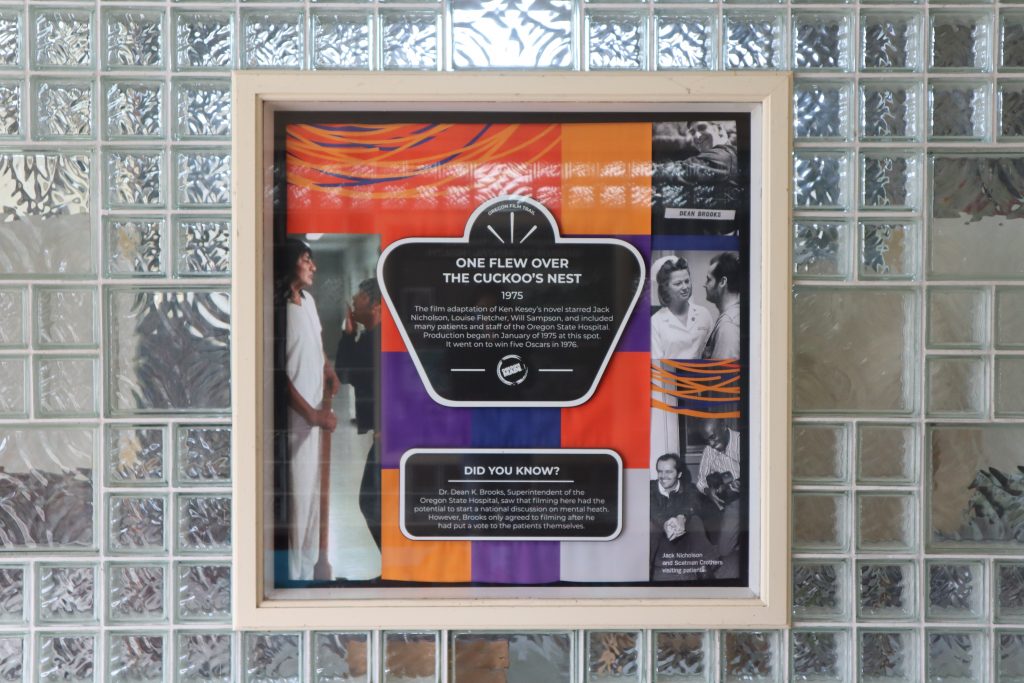

The hospital was also used as the set for the 1975 film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”.

The former Oregon State Insane Asylum now houses the Museum of Mental Health. It looks very similar to how it did in the early 1900s on Wednesday.

Zegers has uncovered some fascinating things.

“I found that Sylvia Plath’s grandmother (Ernestine Plath) died at OSH in 1919 and her cremains were unclaimed until this year. Sylvia was famous for her writing and her struggles with mental illness.”

Zegers said, “Years ago I started doing genealogical research on my own family. I discovered a distant cousin who died at OSH in the 1890s. Her body was claimed, but in learning about her I found out about the 3,500 cans of unclaimed ashes at the hospital. No one asked me to take on the project and I didn’t ask permission – just started doing it.”

The Oregon State Hospital cremated unclaimed bodies. Zegers said, “The ashes are the cremated remains of people who were patients or inmates at various Oregon institutions, but most were patients from Oregon State Hospital, a psychiatric hospital.

“After they died sometimes the institution could find no relatives to notify or sometimes the families declined to receive the body. For whatever reason, if no one claimed the body, they were cremated at OSH. The ashes were put in copper cans that were made by OSH patients. The cans were numbered, logged in a book, and stored away in hopes that at some point a relative would contact the hospital and the ashes could be given to the family.”

Lots of time and research goes into Zegers’ work. In October she was named as one of the recipients of the 2020 Oregon Heritage Excellence Award for her work.

“I decided to research their lives and write a biography for each of them. Initially, my intention was simply to honor each one by posting their life’s story on a memorial page on a website called FindAGrave.com. Then I found with a little more research I could also identify living relatives and contact them in case they would like to know what had happened to their family member,” Zegers said.

The work is deeply educational. Zegers said, “Along the way, I learn a lot about history. The people whose ashes are unclaimed died between 1914 and 1973 and some were born in the early to mid-1800s. Their lives span a wide range of Oregon and U.S. history as well as world history. They came to Oregon from all over the world and engaged in every occupation you can imagine. So in learning about these people I learn so much more.”

She added, “ I enjoy researching each person, but I am especially intrigued with people whose research gives me a peek inside history. For instance, several of the Oregon suffragettes were among the unclaimed and their lives were fascinating.”

Zegers finds the work rewarding. “The most satisfying part is hearing from families who tell me how meaningful it is for them to learn about their relatives. Sometimes the relative is very distant (like a first cousin, three times removed, or great-great-great uncle), but sometimes I am writing to someone about their sibling or grandparent. Often they will tell me that the information answered questions they had had all their lives. Sometimes they say knowing more about this particular person gives them perspective on why other people in the family behaved the way they did. More than once someone has told me they were able to understand and forgive their own parent’s behavior after learning about their grandparent’s mental illness.”

Occasionally, Zegers runs into dead-ends. “It is frustrating when the death certificate has too little information and the name is so common that I have nothing to go on. For some people, I have lots of information but sometimes the more information I have the more questions I have. There will always be unanswered questions.”

Nearly 3,000 unclaimed remains still sit at Oregon State Hospital, waiting to be returned to their family. Hospital officials urge anyone who thinks he or she may have a family member who died while living or working at Oregon State Hospital, Oregon State Tuberculosis Hospital, Mid-Columbia Hospital, Dammasch State Hospital, Oregon State Penitentiary, and Fairview Training Center between 1914 and 1973 to review the list. The list can be reviewed by visiting

https://www.oregon.gov/oha/OSH/Pages/Cremains.aspx

“I enjoy the research process itself and the challenge of discovering as much as possible about these people,” Zegers said. “It’s fun to watch their story become clear. It is like putting together a puzzle or reading a good book.”

Row after row of copper cremains canisters at the Oregon State Hospital Memorial Wednesday in Salem, Oregon.

This wall serves as a memorial while housing the ceramic urns that contain the cremains from OSH Wednesday in Salem, Oregon.

Oxidized copper cans that once held cremains from the “room of forgotten souls” at Oregon State Hospital are now memorialized in Salem, OR on Wednesday.

Close up of some of the thousands of cremains being stored and memorialized at the Oregon State Hospital Memorial Wednesday.